tl;dr. In 2016, the results of a multi-lab preregistered replication effort cast doubt on the idea, motivated by the “facial feedback hypothesis”, that holding a pen with one’s teeth (instead of with one’s lips) makes cartoons appear more amusing. The effect’s progenitor, Dr. Strack, critiqued the replication effort and suggested that the presence of a camera (put in place to confirm that participants held the pen as instructed) makes the effect disappear. This conjecture has recently received some empirical support from a preregistered experiment (Noah et al., 2018, JPSP). Overall, Noah et al. present a balanced account of their findings and acknowledge the considerable statistical uncertainty that remains. It may be the case that the camera matters, although we personally would currently still bet against it. Methodologically, we emphasize how important it is that the confirmatory analysis adheres exactly to what has been preregistered. In order to prevent the temptation of subtle changes in the planned analysis and at the same time eliminate the file drawer effect, we recommend the Registered Report over plain preregistration, although preregistration alone is vastly superior to registering nothing at all.

This tale starts in 2012. Doyen and colleagues had just published a bombshell paper, “Behavioral Priming: It’s All in the Mind, but Whose Mind?” (open access). Here is the first part of their abstract:

“The perspective that behavior is often driven by unconscious determinants has become widespread in social psychology. Bargh, Chen, and Burrows’ (1996) famous study, in which participants unwittingly exposed to the stereotype of age walked slower when exiting the laboratory, was instrumental in defining this perspective. Here, we present two experiments aimed at replicating the original study. Despite the use of automated timing methods and a larger sample, our first experiment failed to show priming. Our second experiment was aimed at manipulating the beliefs of the experimenters: Half were led to think that participants would walk slower when primed congruently, and the other half was led to expect the opposite. Strikingly, we obtained a walking speed effect, but only when experimenters believed participants would indeed walk slower.” (Doyen et al., 2012)

This paper prompted John Bargh to post a blistering personal attack on the authors, and indeed on the journal that had published the work (Bargh’s harsh posts were later removed). Anybody who believes that replications are boring ought to read Ed Yong’s coverage of the row. In our opinion (we are psychologists, after all), anger in the face of replication failure only serves to signal one thing: insecurity. Suppose someone fails to replicate one of your own results, and suppose you are supremely confident that the effect is reliable — say the word frequency effect in lexical decision: high-frequency words such as CHAIR are classified as words faster and more accurately than low-frequency words such as BROUHAHA. What would your response be when someone fails to replicate the word frequency effect? Well, it certainly would not be anger. Perhaps you would feel sorry for the authors (because obviously something had gone wrong in the experiment); perhaps you would shrug your shoulders and move on; perhaps, if the authors were really persistent and if you felt their work was taken seriously by your colleagues, you might become motivated to conduct a study (perhaps in collaboration with the replicators) in order to demonstrate the effect again and prove the replicators wrong. At no point would you feel the need to become angry. So without pretending to have probed deeply into Bargh’s psyche, we submit that he himself is not confident that the effect replicates. And Bargh is not alone; one of the reasons why so many people started to pay attention to these failures to replicate is because the effects were implausible from the get-go. The Doyen paper simply opened the floodgates of doubt, allowing it to be expressed openly. In sharp contrast to what had been advertised in the most prestigious journals in the field, it turned out that the emperor of behavioral priming was rather scantily clad, if clad at all.

Quickly afterwards, the question that arose –partly due to a suggestion by Daniel Kahneman– whether any of the behavioral priming experts were willing to cooperate with a replication attempt of their favorite finding. Especially for those who are insecure, this takes guts; after all, the original author runs the real risk of seeing their favorite finding classified as a non-replicable pollution of the literature. Among the experts, the only person we are aware of who showed such guts at an early stage was Fritz Strack (NB: he was later followed by Ap Dijksterhuis), who volunteered his famous “facial feedback” finding (Strack et al., 1988) for replication. As summarized in Wagenmakers et al. (2016),

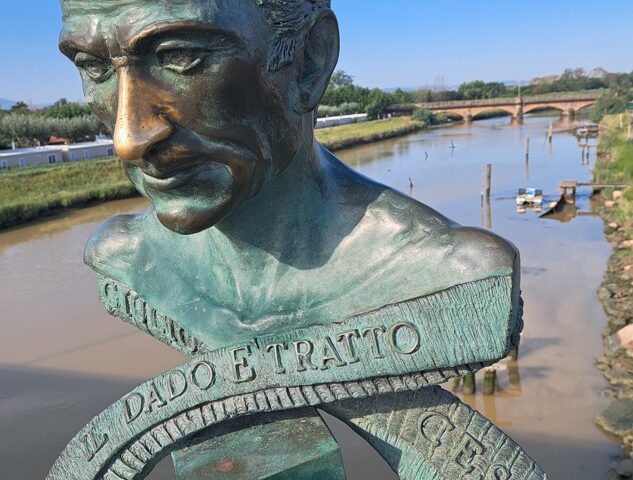

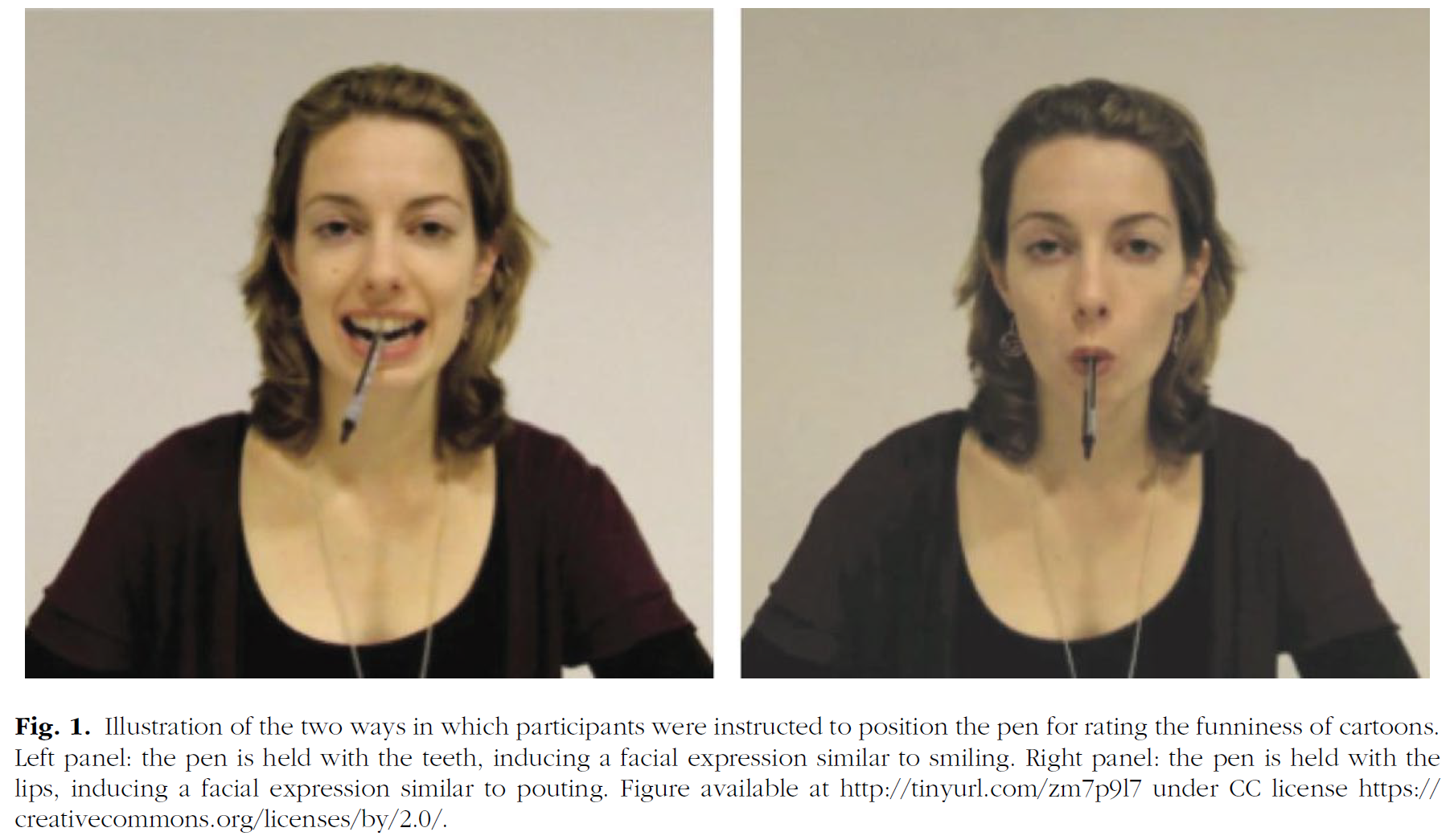

“According to the facial feedback hypothesis, people’s affective responses can be influenced by their own facial expression (e.g., smiling, pouting), even when their expression did not result from their emotional experiences. For example, Strack, Martin, and Stepper (1988) instructed participants to rate the funniness of cartoons using a pen that they held in their mouth. In line with the facial feedback hypothesis, when participants held the pen with their teeth (inducing a “smile”), they rated the cartoons as funnier than when they held the pen with their lips (inducing a “pout”).”

Below is a figure (taken from Wagenmakers et al., 2016) that demonstrates the two key conditions:

So the key empirical question is whether or not participants who hold the pen with their teeth rate cartoons as more amusing than participants who hold the pen with their lips. Note that the cartoons are rated using the same pen, meaning that participants have to bend their head and write “with their mouth” instead of with their hand.

The initial collaboration of Dr. Strack was of key importance as we designed an “RRR”, a Registered Replication Report:

“A central goal of publishing Registered Replication Reports is to encourage replication studies by modifying the typical submission and review process. Authors submit a detailed description of the method and analysis plan. The submitted plan is then sent to the author(s) of the replicated study for review. Because the proposal review occurs before data collection, reviewers have an incentive to make sure that the planned replication conforms to the methods of the original study. Consequently, the review process is more constructive than combative. Once the replication plan is accepted, it is posted publicly, and other laboratories can follow the same protocol in conducting their own replications of the original result. Those additional replication proposals are vetted by the editors to make sure they conform to the approved protocol.” (obtained from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/publications/replication)

When executed correctly, RRRs can provide the strongest and most reliable empirical evidence in existence. RRRs eliminate publication bias, ensure a proper experimental design, rule out statistical cherry-picking, and allow one to explore the extent to which the effect varies across labs all over the world. Setting up an RRR is not an easy task, but when it comes to validating a textbook finding, it is worth it. In fact, we believe that several other textbook findings ought to be inspected using the RRR format.

At any rate, as we started to write our RRR proposal, it became clear that Dr. Strack, despite being very helpful at the start, felt uncomfortable vetting the proposal in more detail. His place was taken by Dr. Ursula Hess, who provided many constructive suggestions for improvement. Specifically, Dr. Hess strongly recommended we use a camera to ascertain that the participants hold the pen as instructed (this will become important later on).

The RRR Results

The facial feedback RRR took an enormous effort to complete, not just in terms of data collection, but also in terms of experimental design and statistical planning. When Eurystheus tried to frustrate Hercules by giving him twelve arduous and near-impossible labors to complete, he was clearly unaware of the possibilities offered by an RRR. Had he known, Eurystheus would have replaced one of the twelve labors by an RRR assignment: “leave this place and do not return until you have conducted an RRR on the facial feedback hypothesis”. Poor Hercules would have needed years to complete this thankless task, not to mention having to face the danger of being driven into bankruptcy due to the spiralling costs for research assistants. Compared to conducting a facial feedback RRR, cleaning out a few stables or strangling the odd lion with one’s bare hands is child’s play. As an aside, an anonymous reviewer once mentioned the facial feedback RRR and concluded it was “shoddy work that was rushed into press”. One imagines a similar response from a grumpy Eurystheus in case Hercules –hair now grey, back bent, and eyes staring blankly ahead– returns after 30 years with the requested RRR: “What, back already, you slacker?” Before we continue, this is the right place to thank research assistants Titia Beek and Laura Dijkhoff for their dedication, expertise, and persistence.

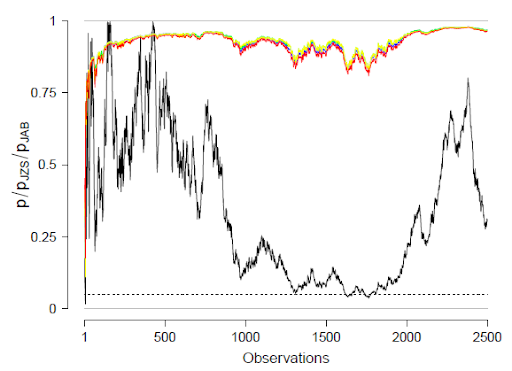

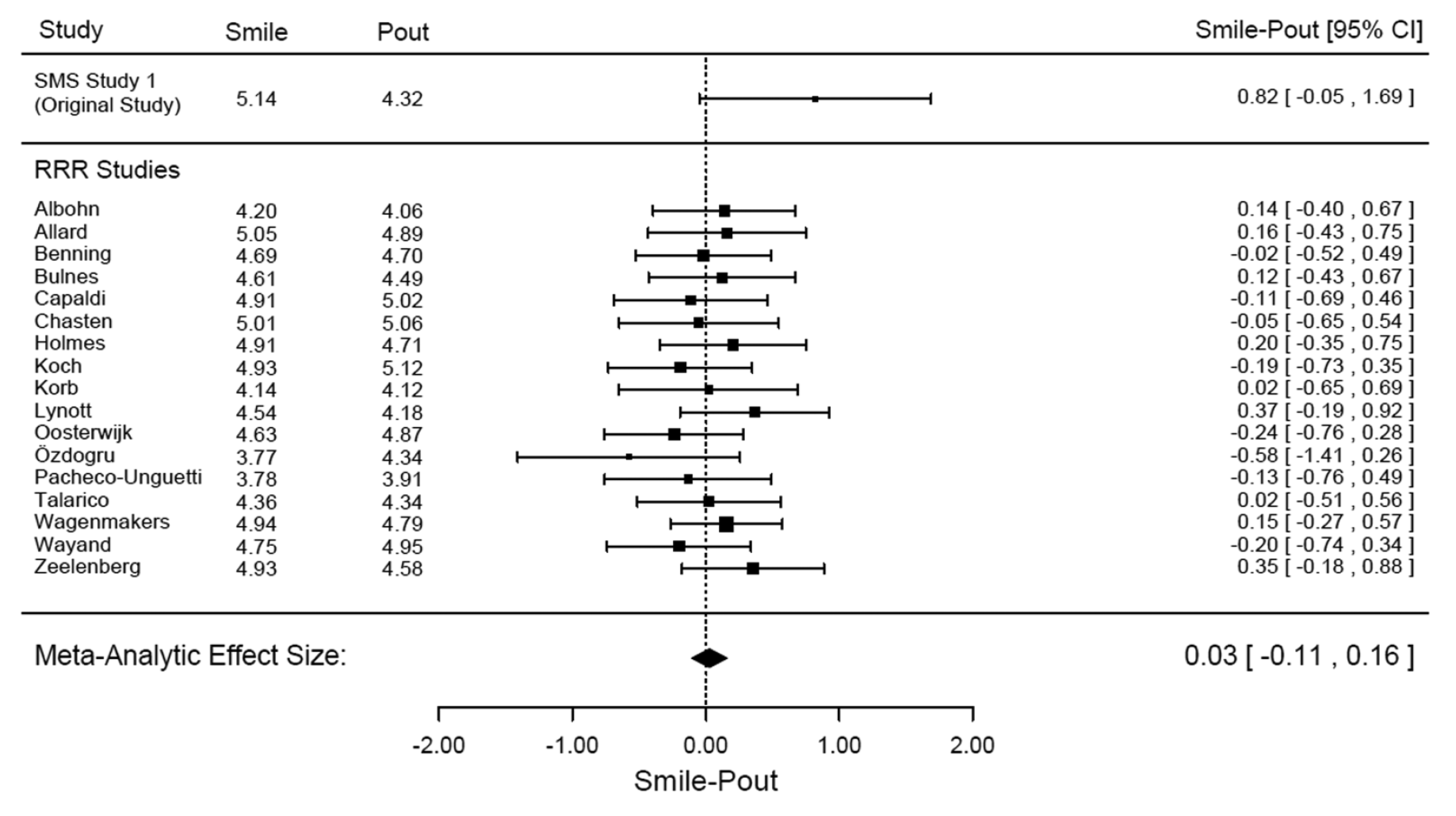

In the end, 17 labs worldwide participated, and this is a summary of the results:

It is immediately apparent that there was no evidence for the effect whatsoever; actually, Bayesian analyses showed there to be evidence in favor of the null hypothesis. The RRR paper is open access and available here.

The Strack Reply

The outcome of the RRR seemed relatively conclusive, and we wondered what Dr. Strack could possibly argue. Well, below are his main points. For the readers’ benefit, we have added our own perspective below each point.

- “Originally, I had suggested the ‘pen study’ to be replicated not only because we (Strack, Martin, & Stepper; SMS) had found the predicted difference but also because numerous operational and conceptual replications from our and our colleagues’ labs have confirmed the original results. During the past 5 years, at least 20 studies have been published demonstrating the predicted effect of the pen procedure on evaluative judgments”

Response: Conceptual replications are never used to falsify a hypothesis, and the file drawer effect will take care of the rest. It is remarkable that there exist very few direct replications of the effect in the literature.

- “First, the authors have pointed out that the original study is “commonly discussed in introductory psychology courses and textbooks” (p. 918). Thus, a majority of psychology students was assumed to be familiar with the pen study and its findings. Given this state of affairs, it is difficult to understand why participants were overwhelmingly recruited from the psychology subject pools. The prevalent knowledge about the rationale of the pen study may be reflected in the remarkably high overall exclusion rate of 24%. Given that there was no funneled debriefing but only a brief open question about the purpose of the study to be answered in writing, the actual knowledge prevalence may even be underestimated.”

Response: In our lab at least, the exclusion rate was high because the camera allowed us to detect that many participants failed to hold the pen as instructed.

- “That participants’ knowledge of the effect may have influenced the results is reflected in the fact that those 14 (out of 17) studies that used psychology pools gained an

effect size of d = −0.03 with a large variance (SD = 0.14), whereas the three studies using other pools (Holmes, Lynott, and Wagenmakers) gained an effect size of d =

0.16 with a small variance (SD = 0.06). Tested across the means of these studies, this difference is significant, t(15) = 2.35, p = .033, and the effect for the nonpsychology studies significantly deviates from zero, t(2) = 5.09, p = .037, in the direction of the original result.”Response: This post-hoc analysis cherry-picks among a homogeneous set of studies. Also, the reanalysis compares the study means without taking into account the variability with which these means are estimated. More importantly, Dr. Strack implies that subject-pool psychology students know the effect but report not knowing it, and that this implicit knowledge of the facial feedback effect somehow prevents it from manifesting itself. Possible, perhaps, but rather implausible.

- “Second, and despite the obtained ratings of funniness, it must be asked if Gary Larson’s The Far Side cartoons that were iconic for the zeitgeist of the 1980s instantiated similar psychological conditions 30 years later. It is indicative that one of the four exclusion criteria was participants’ failure to understand the cartoons.”

Response: As mentioned in the RRR article:

“First, we selected and normed a new set of cartoons to ensure that those used in the study would be moderately funny, thereby avoiding ceiling or floor effects. Twenty-one cartoons from Gary Larson’s The Far Side were rated by 120 psychology students at the University of Amsterdam on a scale from 0 (not at all funny) to 9 (very funny). We selected four cartoons that were judged to be ‘moderately funny.’ Ratings for the complete set of cartoons are available on the OSF.”

So the cartoons were preselected to be medium funny. Moreover, the ratings themselves are very close to those reported for the Strack et al. (1988) The Far Side cartoons. There appears to be no basis for the claims that the cartoons are processed in a fundamentally different way. Moreover, The Far Side cartoons we used are timeless, and it is difficult to see how they capture the “zeitgeist from the 1980s”. One cartoon has two monkeys dancing, and one says to the other “I’m afraid you misunderstood….I said I’d like a mango.” Another cartoon features a cowboy with a ream of toilet paper stuck to his spurs (“Nerds of the Old West”); another shows three fish who find themselves outside their bowl that has caught fire (“Well, thank God we all made it out in time….’Course, now we’re equally screwed.”); the final cartoon shows a woman admonishing a cat; “what we say to cats” contains a text field with a lengthy dialogue; “what they hear” shows the same panel but now with an empty text field.

- “Third, it should be noted that to record their way of holding the pen, the RRR labs deviated from the original study by directing a camera on the participants. Based on

results from research on objective self-awareness, a camera induces a subjective self-focus that may interfere with internal experiences and suppress emotional responses.”Response: This is a remark that we will discuss later in more detail. It is important to note that the expert who vetted the protocol strongly recommended we add the camera, because by excluding participants who failed to hold the pen correctly we could reduce noise and maximize the chances of finding the effect. And indeed, it turned out that holding the pen correctly (while “mouth-writing” the cartoon’s rating) was rather difficult, and many participants needed to be excluded. We still believe that using the cameras was a good idea.

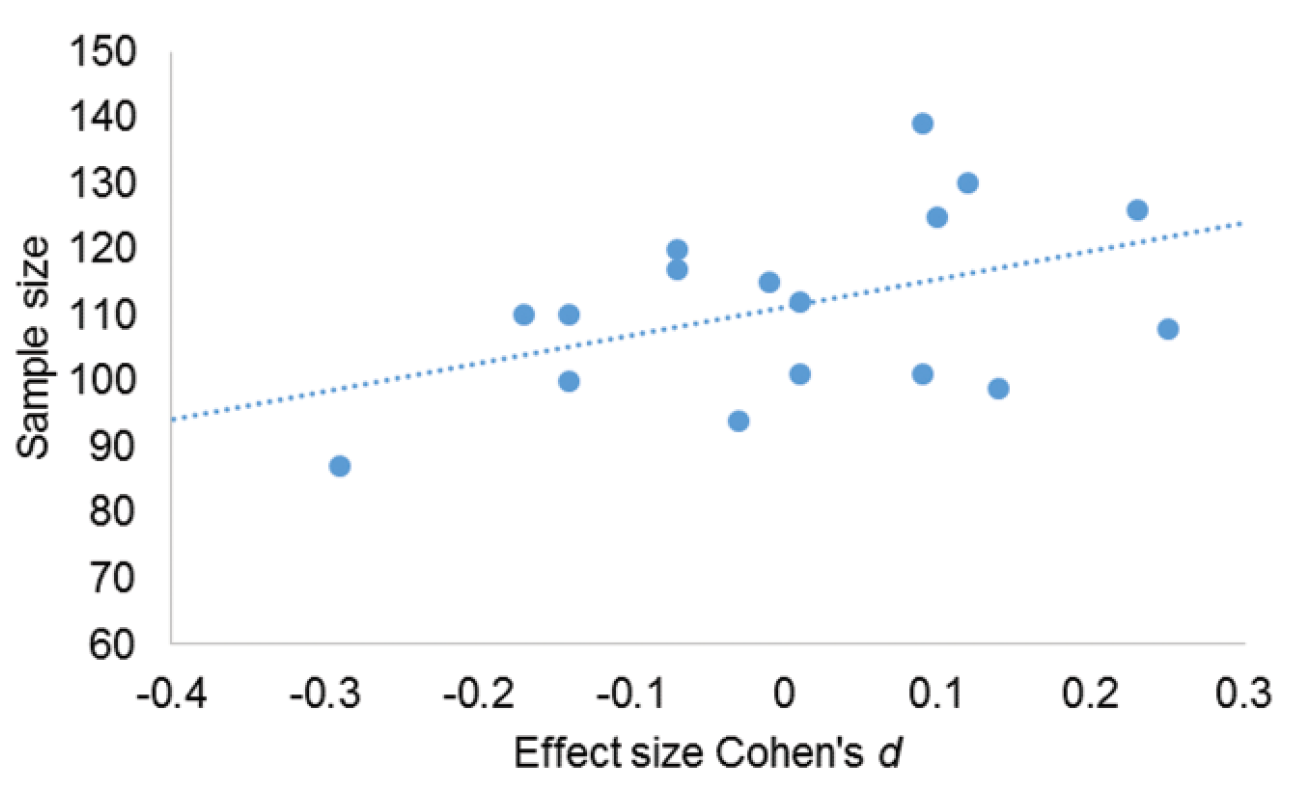

- “Finally, there seems to exist a statistical anomaly. In a meta-analysis, when plotting the effect sizes on the x-axis against the sample sizes on the y-axes across studies, one should usually find no systematic correlation between these two parameters. As pointed out by Shanks and his colleagues (e.g., Shanks et al., 2015), a set of unbiased studies would produce a pyramid in the resulting funnel plot such that relatively high-powered studies show a narrower variance around the effect than relatively low-powered studies. In contrast, an asymmetry in this plot is seen to indicate a publication bias and/or p hacking (Shanks et al., 2015). Figure 1 displays the funnel plot for the present 17 Studies.

Obviously, there is no pyramidal shape of the funnel. Although all of the present studies were appropriately powered, there were several relatively low-powered unsuccessful studies (at the left bottom) but only a few relatively low-powered successful studies (at the right bottom). This is reflected in a relationship between effect size and sample size, r(17) = .45, p = .069, such that the size of the sample is positively correlated with the size of the effect. Note that this pattern is the opposite of what is usually interpreted as a publication bias or p hacking in favor of an effect (resulting in a negative correlation between effect size and sample size). Without insinuating the possibility of a reverse p hacking, the current anomaly needs to be further explored.”

Response: Without insinuating that Dr. Strack wrote his reply in bad faith, it needs to be pointed out that all of the statistical analyses were preregistered and battle-tested on a mock data set. Even the interpretation of the results had been preregistered. The analysis of the real data therefore proceeded mechanically and there was not a smidgen of room for cherry-picking or skewing the interpretation of the result. Having ruled out “reverse p-hacking”, what could account for the anomaly that Dr. Strack identified? Well, the anomaly is not an anomaly at all; it is a mirage. To appreciate this, note that the differences in power are minute. Almost all sample sizes fall between 95 and 120. With so little variability, one would not expect to find a nice funnel plot shape. So the ‘anomaly’ is probably just noise. Moreover, the relation is not statistically significant; and even if it were, it is entirely post-hoc and so the presented p-value is meaningless. Ironically, it is Dr. Strack’s analysis that is p-hacked, in the sense that he looked at the data, the data gave him a hypothesis (‘hey, whad’ya know, it looks like the relationship between sample size and effect size appears to be linear’), and then he tested that hypothesis using the same data that gave him the idea. You can’t do that. Well you can, but it is statistically incorrect.

Finally, we asked participants whether or not they understood the cartoons because for some participants English was not their native language.

Interim Summary

The comprehensive RRR non-replication casts doubt on the utility of the Strack pen paradigm, but of course it does not refute the facial feedback hypothesis in general; this is something that awaits further research.

The fact that Dr. Strack chose not to vet the protocol allowed him the freedom to critique design decisions post-hoc. For instance, if the RRR had excluded the camera, Dr. Strack could have argued that without the watchful eye of an experimenter, many participants may not have held the pen correctly, polluting the data set. Nosek and Lakens (2014, p. 138) have termed this CARKing, ‘critiquing after the results are known’ (after Kerr’s HARKing, ‘hypothesizing after the results are known’). Nevertheless, Dr. Strack’s suggestion that the camera made the effect disappear was taken up by other researchers, and the result of their efforts has just been published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (JPSP). We discuss this work below.

New Empirical Evidence: Does a Camera Block the Effect?

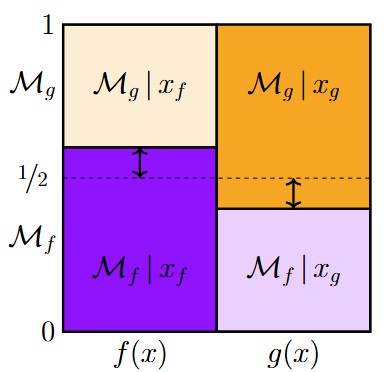

In a recent development, Noah et al. (2018) published an article in JPSP that explicitly manipulates the presence of a camera. Based on the RRR, the Noah experiment features two groups of participants, one in the teeth condition and one in the lips condition. However, in addition, one set of participants had a camera in their booth (unbeknownst to the participant, the camera did not record anything), and the other set did not. So we have a classic 2 x 2 between-subjects experimental design with four groups of participants: “teeth condition with camera”, “teeth condition without camera”, “lips condition with camera”, and “lips condition without camera”. The authors also preregistered their experiment, hypothesis, and analysis plan (!). With respect to the analysis plan, they preregistered the following:

“We will conduct a between participants 2 way ANOVA (Camera presence [yes / no] x Facial activity [lips / teeth]) on the average rating of the four cartoons (excluding cartoons that each participant will report s/he did not understand). Based on the facial feedback effect (Strack et al., 1988), we hypothesize that in the no-camera condition, the cartoons would be rated as funnier in the teeth condition than in the lips condition. We predict that this effect will be smaller (or non-existent) in the camera condition, as will be indicated by an interaction effect.”

And here are the authors’ findings, in their own words:

“The results revealed a significant facial-feedback effect in the absence of a camera, which was eliminated in the camera’s presence. These findings suggest that minute differences in the experimental protocol might lead to theoretically meaningful changes in the outcomes.” (Noah et al., 2018, abstract)

Now the authors are somewhat overstating their case. For instance, the authors conducted a Bayesian analysis, and in the no-camera condition they report a Bayes factor of 8.66 in favor of the facial feedback effect. They then provide a word of caution:

“Even a highly diagnostic statistical outcome, such as BF = 8.66, should be interpreted probabilistically, meaning that one should remember that the probability of making the wrong inference is not negligible (10% in the case of BF = 8.66).”

But a BF of 8.66 is not “highly diagnostic”; if the prior model probability for the alternative hypothesis is 50%, a BF of 8.66 raises this to 8.66/9.66 = 90%, still leaving 10% for the null hypothesis, as the authors imply. A BF of 8.66 is definitely evidence worthy of reporting; we may not have protested in case the authors had preregistered a sequential Bayesian analysis with a BF of 8 as a stopping criterion. Nevertheless, a 10% chance for the null hypothesis still leaves considerable room for doubt, as Noah et al. duly acknowledge. But we don’t want to nitpick (too much). The authors helpfully divide their results section in a section “Confirmatory analysis” and “Exploratory analysis”. This is good practice. Let’s consider the business end of the confirmatory section in detail:

“According to the main hypothesis of this research, both analyses [ANOVA and Bayes factors — EJ&QFG] indicated that in the no-camera condition, as in the study by Strack et al. (1988), the participants in the teeth condition rated the cartoons as significantly more amusing than did participants in the lips condition (Mteeth = 5.75, SD = 1.35, Mlips = 4.92, SD = 1.46), t(162) = 2.48, p = .01, η2p = .038, 95% confidence limits: [.171-1.500], BF = 8.66. In the camera-present condition, similar to the findings of Wagenmakers et al. (2016), this difference was much smaller and nonsignificant (Mteeth = 5.21, SD = 1.46, Mlips = 5.15, SD = 1.74), t(162) = .19, p = .85, η2p < .001, 95% confidence limits: [-.586 -.712], BF = 0.364. Are the two simple effects different from each other? Although the test of the 2 x 2 interaction was greatly underpowered, the preregistered analysis concerning the interaction between the facial expression and camera presence was marginally significant in the expected direction, t(162) = 1.64, p = .051, one-tailed, η2p = .016, BF = 2.163. As predicted, the analysis did not reveal any main effect of camera presence or of facial feedback.”

Now consider an alternative section, one which is arguably more in line with the preregistration document:

“Our preregistration document specified the test of an interaction in a 2 x 2 ANOVA. We carried out the planned analysis and the interaction was not significant, p > .10.”

The real problem here is twofold. First of all, the authors may not have given their planned analysis sufficient thought. The only preregistered analysis concerned “an interaction effect” in a 2 x 2 ANOVA. We are willing to cut Noah et al. some slack because their preregistration document is consistent with the idea that the facial feedback effect ought to be present in the no-camera condition, and absent or smaller in the camera condition. But this relates to the second problem: the authors should not have cut themselves this slack. They made the mistake of preregistering the interaction test, and only the interaction test. There may be good reasons to conduct tests other than the one that was actually preregistered, but none of these reasons warrant the intrusion of such tests into the section “Confirmatory Analysis”. Also note that once the two non-preregistered infiltrator tests are allowed, we now have three tests, and one may start to wonder about corrections for multiple testing. The authors do address this issue explicitly, saying:

Although the interaction is useful for showing the role of the presence of a camera in this paradigm, it is not critical for our argument. That is, our argument is not about the specific effect of the presence of a camera, but rather, about the consequences of its absence—the existence of the facial feedback effect” (Noah et al., 2018, p. 659)

So it appears that the only analysis the authors preregistered is one that is “not critical” to their argument. Now imagine the hypothetical scenario where the interaction would have been statistically significant, but the t-test for the camera-absent condition would have yielded p > .10 (and a one-sided p = .051). Would the authors still have argued that the preregistered analysis is not critical to their argument? There is no way to tell, but we find it hard to believe. Moreover, the article very much reads as if the effect of the presence of the camera is in fact crucial, because, as the title “When both the original study and its failed replication are correct” suggests, it acts as an explanation as to why the effect was absent in the RRR but present in Noah et al.

Take-Home Message

The Noah et al. manuscript has taught us a few lessons about preregistration. First and foremost, preregistration is essential because without it, you have no clue of the extent to which the data were tortured to obtain the reported result. OK, this we already knew. But the importance of this fact became more apparent when we realized that the Confirmatory Analysis section had been infiltrated by analyses that had not been preregistered, but only hinted at. Moreover, these non-preregistered analyses form the very basis for the authors’ conclusion. Without a preregistration form, it would have been impossible to distinguish the infiltrators from the real preregistered deal. This brings us to the second lesson: even after being attended to the discrepancy (in the review process, by one of us), the authors still could not bring themselves to acknowledge that their planned analysis yielded p > .10. Perhaps this sort of preregistration policing should be left to the reviewers. Ideally, the reviewers are involved in the entire process, from the design stage onward, and have to indicate, explicitly, whether or not the authors carried out the intended analysis. This a key ingredient of Chambers’ Registered Report format, which is now offered by over 100 journals. The other key ingredient of the Registered Report is that publication is outcome-independent; this means that if one examines whether camera’s influence the facial feedback effect, and the result comes up negative, the finding will still be published. And this is of course the other problem with the interpretation of the Noah et al. paper — we need to know how many other experiments have tried to test whether the effect can be found without the cameras.

In sum, the Noah et al. article presents a glimmer of hope for the aficionados of the Strack pen paradigm. We would still bet against the effect, however, with or without a camera present, but only the future can tell. The main contribution of the Noah et al. article, however, may prove to be methodological: it demonstrates the urgent need to preregister one’s hypotheses carefully and comprehensively, and then religiously stick to the plan (see also this post) As was done in the facial feedback RRR, the best method may be to generate a mock data set and create all analysis code and possible conclusions in advance of data collection.

(See below for a response by Yaacov Schul, Tom Noah, and Ruth Mayo.)

Like this post?

Subscribe to the JASP newsletter to receive regular updates about JASP including all its Bayesian analyses! You can unsubscribe at any time.References

Doyen, S., Klein, O., Pichon, C. L., Cleeremans, A. (2012). Behavioral priming: Its all in the mind, but whose mind? PLoS ONE, 7, e29081. Open Access.

Noah, T., Schul, Y., & Mayo, R. (2018). When both the original study and its failed replication are correct: Feeling observed eliminates the facial-feedback effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114, 657-664. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000121

Nosek, B. A., & Lakens, D. (2014). Registered Reports: A method to increase the credibility of published results. Social Psychology, 45, 137-141.

Strack, F. (2016). Reflection on the smiling Registered Replication Report. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 929-930. Open Access.

Strack, F., Martin, L. L., & Stepper, S. (1988). Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: A nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 768-777.

Wagenmakers, E.-J., Beek, T., Dijkhoff, L., Gronau, Q. F., Acosta, A., Adams, R. B., Jr., Albohn, D. N., Allard, E. S., Benning, S. D., Blouin-Hudon, E.-M., Bulnes, L. C., Caldwell, T. L., Calin-Jageman, R. J., Capaldi, C. A., Carfagno, N. S., Chasten, K. T., Cleeremans, A., Connell, L., DeCicco, J. M., Dijkstra, K., Fischer, A. H., Foroni, F., Hess, U., Holmes, K. J., Jones, J. L. H., Klein, O., Koch, C., Korb, S., Lewinski, P., Liao, J. D., Lund, S., Lupianez, J., Lynott, D., Nance, C. N., Oosterwijk, S., Ozdogru, A. A., and Pacheco-Unguetti, A. P., Pearson, B., Powis, C., Riding, S., Roberts, T.-A., Rumiati, R. I., Senden, M., Shea-Shumsky, N. B., Sobocko, K., Soto, J. A., Steiner, T. G., Talarico, J. M., van Allen, Z. M., Vandekerckhove, M., Wainwright, B., Wayand, J. F., Zeelenberg, R., Zetzer, E. E., & Zwaan, R. A. (2016). Registered Replication Report: Strack, Martin, & Stepper (1988). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 917-928. Open Access.

About The Authors

Eric-Jan Wagenmakers

Eric-Jan (EJ) Wagenmakers is professor at the Psychological Methods Group at the University of Amsterdam.

Quentin Gronau

Quentin is a PhD candidate at the Psychological Methods Group of the University of Amsterdam.

Response by Yaacov Schul, Tom Noah, and Ruth Mayo

Our paper advocates cooperation in research. As we wrote in the Discussion section, we believe that “There is no doubt that the field of psychology has made substantial advances in promoting the understanding of the way we should do and report research. However, this has come at a cost. It has introduced a focus on good versus bad researchers rather than on the research. Debates about scientific questions turn into an issue of us-against-them. The unfortunate outcome of this state of affairs is a decrease in cumulative science. Controversies about whose findings are correct almost necessarily preclude a conclusion that both sides might be correct.” Thus, we appreciate very much the opportunity to respond. We shall start by commenting on the sections referring to our own research. Then, we shall make a few general comments.

The report of the planned analysis. It is suggested that the appropriate description of our finding should be “We carried out the planned analysis and the interaction was not significant, p > .10”. We believe this is wrong. Although we do refer to an interaction within a 2×2 ANOVA, we test a particular pattern of an interaction, predicted a priori by the theoretical analysis. That is, whereas the test of interaction within an ANOVA framework tests any departure from additivity (a non-directional interaction), our planned analysis, based on our stated theoretical claims, involved a planned interaction contrast. Therefore, the p-value was adjusted. In addition, we were criticized for reporting the two simple effects. It is true that in the section of the statistical analysis we did not specify the tests of the simple effect. But these tests were clearly set up in the introduction section. Specifically we hypothesized, based on the research we cite, the presence of the facial feedback effect when participants are not monitored by videotaping. Furthermore, based on the findings in Tom Noah’s Ph.D. which demonstrate that the reliance on meta-cognition weakens when one is in an observed state of mind (Noah, Schul & Mayo, JEP:G, in press), we hypothesized that the facial-feedback effect would diminish in the camera condition. Accordingly, we believe that the two simple-effect hypotheses concerning the existence of the facial feedback effect in the no-camera condition and its absence in the camera condition, were fully set up in the introduction section. This was our main goal (and we should add, this was the one and only study we conducted regarding the facial feedback effect). Therefore, we submit that calling the tests of two simple-effect hypotheses “non-preregistered infiltrator tests” is an exaggeration.

Interpretation of BF=8.66. We are criticized for calling a BF of 8.66 “highly diagnostic”. BF = 8 can be interpreted as suggesting that the data are 8 times more likely to come from the experimental hypothesis than from the alternative (null in this case) hypothesis, when prior to the data collection one does not favor one hypothesis or the other. Moreover, Wetzels, Matzke, Lee, Rouder, Iverson, & Wagenmakers (2011) describe BF in the [3-10] interval as providing substantial evidence for the hypothesis and BF > 10 as providing strong evidence for the hypothesis. It is up to the reader to decide whether these characteristics are rightfully described as highly diagnostic. More generally, we believe that as long as the summary data and the test statistics are given faithfully, and especially, when the reader has access to the original data, a discussion about the adjectives used to describe the data is not very productive.

General comments

The blog entry makes suggestions to the way we should do science. We applaud this perspective, since we are also concern with the way our community acts. In particular, we worry about whether the current publication procedures are optimal in terms of producing valid scientific findings. The entry advocates the importance of preregistration-related policing effort, suggesting that “Perhaps this sort of preregistration policing should be left to the reviewers. Ideally, the reviewers are involved in the entire process, from the design stage onward, and have to indicate, explicitly, whether or not the authors carried out the intended analysis.”

Let us make two comments regarding this suggestion. First, consider a more radical suggestion: Instead of publishing research in fixed-space outlets (i.e., paper journals), perhaps the community should switch to publication in unlimited-space outlets (i.e., cloud depository of research projects). Moreover, instead of having very few enforcers of quality (i.e., reviewers), let all the people in a relevant community be able to comment on the quality of each research project. In short, what we are suggesting is a large depository (or many depositories) of unpoliced research projects, each consisting of many research reports and their data. The reports may provide explicit links to relevant research. Readers (perhaps qualified by some formal criteria) might be able to “vote” on each such project, thus providing a summary quality assessment. We are quick to point out that the wisdom of the masses cannot replace the wisdom of the single reader who can see the research project from a perspective unnoticed by the masses. We believe that variants of the abovementioned suggestion would preempt the need for preregistration-related policing practices. Moreover, history teaches that policing attempts often create counter-attempts to outmaneuver them. As we note in our introductory comment, research must be built on trust. Clearly, there are a few corrupt individuals in our community, and there are many others who are uneducated to different degrees about methodology. As the recent methodological campaign has shown, ignorance can be rectified by education. Trying to change practices by various acts of force can backfire badly.

The second general comment concerns the focus on methodology. The blog suggests that “The main contribution of the Noah et al. article, however, may prove to be methodological: it demonstrates the urgent need to preregister one’s hypotheses carefully and comprehensively, and then religiously stick to the plan”. As the last section of our paper emphasizes, the psychology of experimentation should be brought to bear when we interpret our findings. There is ample research about the role of culture, individual differences, participants’ expectations, and the subjective experimental context on people’s reactions. Often these may not be apparent prior to data collection, and there must be a way to incorporate them when trying to understand the data. Clearly, this leaves a lot of undesirable freedom to the researchers, which should be limited. Indeed, many excellent changes concerning doing research and the report practices have been offered in recent years in order to curtail this undesirable freedom. However, we submit that the other extreme view, namely forbidding researchers from bringing insights gained from the moment they started their experiments to the writing of the manuscript, is undesirable as well. We are well aware that this position is currently an unpopular view. Still, we believe that the pendulum swung too far. It seems that pre-registration in the form suggested in the blog entry, encourages researchers to think only before they run the study and not a minute after. We would like to end this point by reminding readers of this blog entry that our study was not about the importance of preregistration. In addition to the potential contribution for understanding the facial-feedback effect, our paper highlights the richness of the factors that are involved in determining human behavior. One implication of this view is that exact replications are never exact and caution should be exercised in interpreting replication results. Another implication is that although planned and post-hoc knowledge must be clearly demarcated in research reports, neither should be abandoned in analyzing findings and reporting about them.

Finally, let us comment about the style of this discussion. It has been said that death and life are in the power of the tongue. Whereas the general tone of this blog post is balanced, we believe it is wrong to discuss personalities or make personal attributions haphazardly. In particular, a sentence like “In our opinion (we are psychologists, after all), anger in the face of replication failure only serves to signal one thing: insecurity.” should be used only when it is backed by ample evidence. We believe that the precision one requires from reports of research findings should be echoed in the way we write about science.