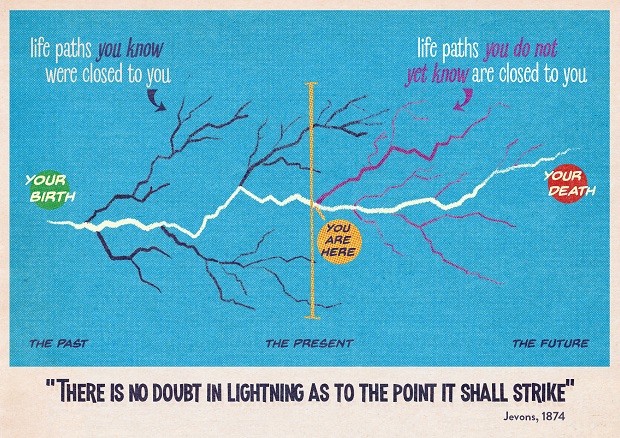

Many people believe that the future is partly in their own hands. We can usually choose freely whether to watch TV, or read a book, or go to the movies; we decide where to go on vacation, what to eat, whom to marry, and so on. There appears to be no external authority who commands us in such decisions, big and small; in this sense we can do what we want. This ‘free will’ perspective suggests that many possible futures remain open to us, and that we are in control of our own destiny, at least to some degree. A figure that represents this perspective is available here and formed the inspiration for this post.

The fact that we can do what we want, however, does not present a compelling argument against determinism. Yes, we may watch TV because we feel like it — but where did that feeling come from? A determinist believes that ‘free will’ is merely an illusion. You may experience the desire to do something and then do it, but that desire itself is the inevitable result of a myriad causal factors that were set in motion since the beginning of time. As summarized by Schopenhauer: “You can do what you will: but at each given moment of your life you can will only one determined thing and by no means anything other than this one.”

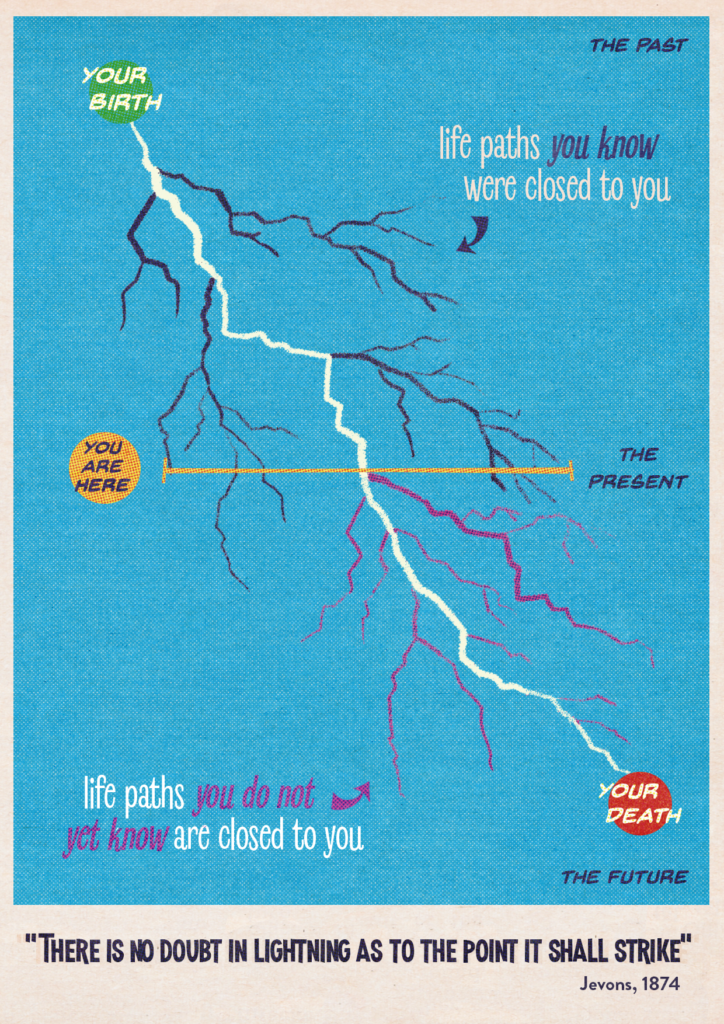

This deterministic perspective on life is visualized in the figure below. The artwork is by Vikor Beekman, and it is available under a CC-BY license in our Artwork Library.

The white lighting bolt running from top to bottom represents your life path, from which no deviation whatsoever is possible. The black lightning bolts in the top panel represent alternative life paths that you now know were always closed to you. It is not just that these alternative realities did not happen; they could never have happened. For instance, it would be tempting to think “had I not folded my hand but called her bluff instead then I would have won the poker tournament”; instead, the correct deterministic thought is “I now know that I did not call her bluff, and did not win the poker tournament”. The purple lighting bolts in the bottom panel represent alternative life paths that you do not yet know will never materialize. It is tempting to think “If I participate in this lottery and I’m lucky, I may win the jackpot”; a determinist would correct this to “I do not yet know whether or not I will win the lottery. However, this is not an eventuality or a matter of luck — it is a certainty, but one of which I will only become aware after the fact.”

An apt analogy is presented by Schopenhauer: “(…) we ought to regard events as they occur with the same eye as the print that we read, knowing full well that it stood there before we read it.” When in the middle of a book, you know how the story started but you are still unsure about how it will end — but it can end in only one way, just as it started in only one way. For a determinist, the difference between what lies in the past and what lies in the future can therefore be attributed solely to a difference in knowledge.

References

Jevons, W. S. (1874/1913). The Principles of Science: A Treatise on Logic and Scientific Method. London: MacMillan.

Schopenhauer, A. (2009). The Two Fundamental Problems of Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. The original German edition dates from 1841 and is entitled Die Beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik.

About The Author

Eric-Jan Wagenmakers

Eric-Jan (EJ) Wagenmakers is professor at the Psychological Methods Group at the University of Amsterdam.