This post is an extended synopsis of Hoogeveen, S., Wagenmakers, E.-J., Kay, A. C., & van Elk, M. (in press). Compensatory Control and Religious Beliefs: A Registered Replication Report Across Two Countries. Comprehensive Results in Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/

23743603.2019.1684821

Abstract

Compensatory Control Theory (CCT) suggests that religious belief systems provide an external source of control that can substitute a perceived lack of personal control. In a seminal paper, it was experimentally demonstrated that a threat to personal control increases endorsement of the existence of a controlling God. In the current registered report, we conducted a high-powered (N = 829) direct replication of this effect, using samples from the Netherlands and the United States (US). Our results show moderate to strong evidence for the absence of an experimental effect across both countries: belief in a controlling God did not increase after a threat compared to an affirmation of personal control. In a complimentary preregistered analysis, an inverse relation between general feelings of personal control and belief in a controlling God was found in the US, but not in the Netherlands. We discuss potential reasons for the replication failure of the experimental effect and cultural mechanisms explaining the cross-country difference in the correlational effect. Together, our findings suggest that experimental manipulations of control may be ineffective in shifting belief in God, but that individual differences in the experience of control may be related to religious beliefs in a way that is consistent with CCT.

To assess the existing evidence for the experimental effect of a personal control threat on belief in a controlling God, we first conducted a Bayesian reanalysis and meta-analysis (Gronau et al., 2017; Scheibehenne, Gronau, Jamil, & Wagenmakers, 2017) of previous findings in the literature.

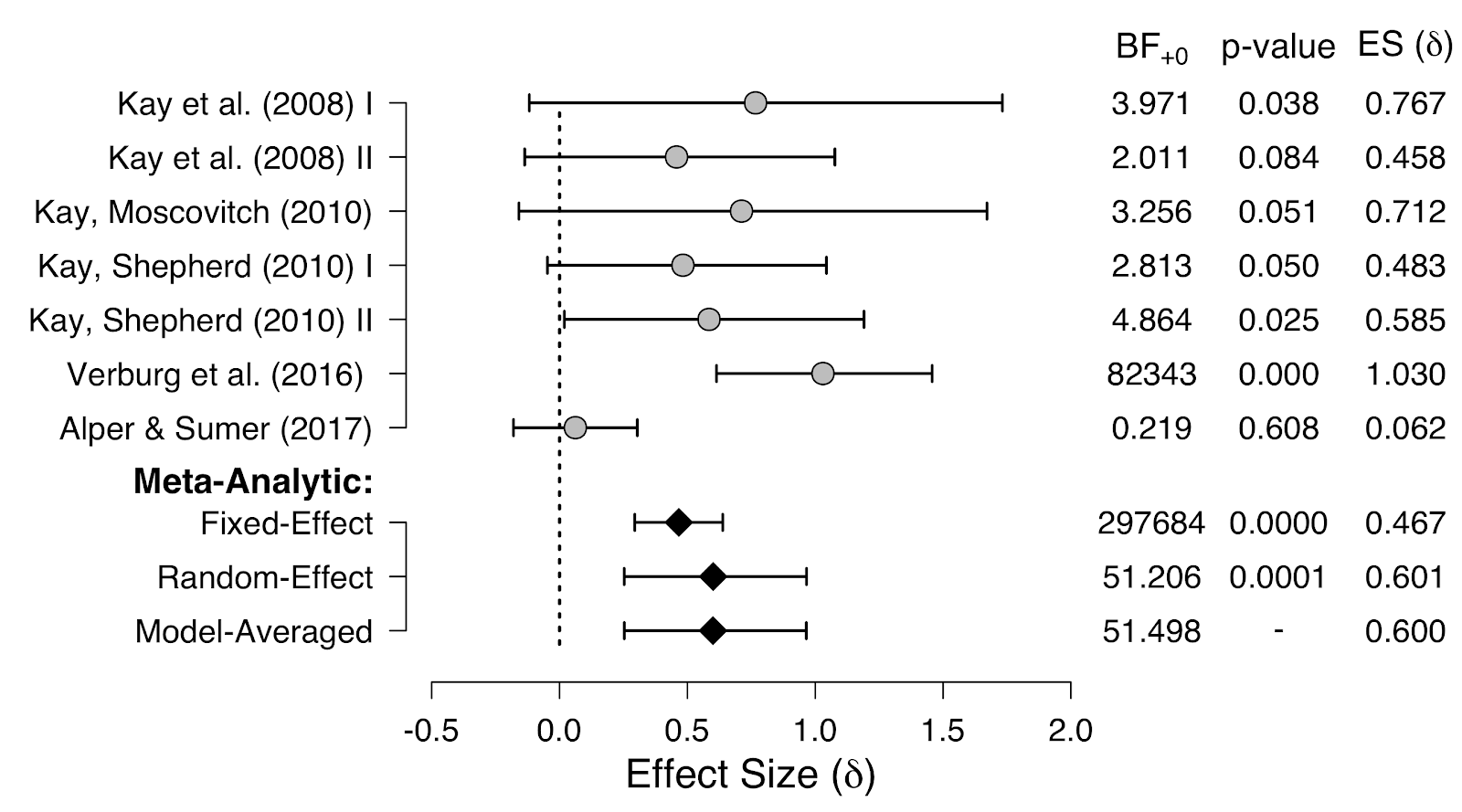

Figure 1. Summary of previous studies plus meta-analysis on the effects of control threat on belief in a controlling God. The Bayes factor M+0 quantifies the evidence that the data provide for H+ (i.e. the presence of the compensatory control effect) relative to H0 (i.e. the absence of the compensatory control effect). Created using the metaBMA R package (Gronau et al., 2017; Heck & Gronau, 2017). Exact p-values were not always given in the articles, but were recalculated based on the reported statistics, converting the one-way ANOVA F-values to t-values. For Kay et al. (2010), the misattribution (i.e. no anxiety) condition is excluded.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the data from most studies provide only weak evidence for the effect of personal control threat on belief in a controlling God. Specifically, based on the commonly used interpretation categories of Bayes factors (e.g. Lee & Wagenmakers, 2013, p. 105; Jeffreys, 1939), the studies by Kay et al. (2008, 2010, 2010) all yielded evidence that is considered anecdotal to moderate. Only the findings by Verburg et al. (2016) yielded compelling evidence for the control threat effect on religious belief. The study by Alper and Sümer (2017), on the other hand, appears to provide moderate evidence against the presence of the effect. Overall, our Bayesian meta-analysis indicates strong evidence in favor of the presence of a control threat effect on belief in a controlling God. However, our meta-analysis also suggests that there is substantial heterogeneity; the random effects model has far more predictive adequacy than the fixed effects model, hence, the averaged model is primarily determined by the random effects model. Furthermore, the credible interval of the average meta-analytic effect size is rather large; CI ranges from 0.250 to 0.962, with a median of δ = .600. This further supports the motivation to conduct the high-powered proposed replication study.

For our own data, we similarly conducted Bayesian analyses to investigate the primary experimental effect and a potential interaction effect for the Dutch and the American sample.

Experimental effect

In order to quantify the evidence for the control threat effect on belief in a controlling God, we compared the model including only religiosity (Mcov) to the model including religiosity and control condition (Mexp). In the Netherlands, we found a Bayes factor of 0.18 in favor of Mexp over Mcov ;BF+0 = 0.18 (i.e. the evidence for the null hypothesis was: BF+0 = 5.41). This means that the data are about 5.41 times more likely under the null model including only religiosity, compared to the alternative model that also includes the control-threat manipulation. This is constitutes moderate evidence against an effect of control threat on belief in a controlling God. In the US, a similar pattern was observed; BF+0 = 0.09 (i.e. BF+0 = 11.16) indicates strong evidence for the null hypothesis over the experimental hypothesis that the control threat manipulation resulted in heightened belief in a controlling God. Following the analysis plan, these findings are taken as “replication failure” for the experimental control threat effect on belief in a controlling God.

Interaction effect

Although we did not find a main effect of control condition on belief in a controlling God, there may have been an interaction between religiosity and control condition, e.g., the control-threat effect could be present only for those who are already strongly religious. In order to investigate this possibility, we compared Mexp to the model including religiosity, control condition, and the interaction between religiosity and control condition (Mfull). This yielded no evidence for an interaction effect: BF10 = 1.72 for Mfull relative to Mexp in the Netherlands. In the US, we found a BF01 = 0.10 for the Mfull relative to Mexp (i.e. BF01 = 10.16), indicating strong evidence in favor of the no-interaction hypothesis.

Posterior model probabilities

Assuming equal prior probabilities for all three models and using Bayes’ rule, the posterior model probabilities are 0.744 and 0.889 for Mcov , 0.094 and 0.101 for Mexp, and 0.162 and 0.010 for Mfull, for the Netherlands and the US, respectively (see Table 1). These results demonstrate again that the religiosity-only model predicted the observed data better than the control threat model and the full model.

Table 1. Posterior model probabilities.

| Netherlands | United States | |

|---|---|---|

| Religiosity Only | 0.744 | 0.889 |

| Religiosity + Control | 0.094 | 0.101 |

| Religiosity + Control + Religiosity*Control | 0.162 | 0.010 |

| Note. All three models were assumed to be equally likely a priori. |

Correlational effect

In addition to the experimental hypothesis, we assessed the relationship between feelings of personal control and belief in a controlling God. As we expected a monotonic, but not necessarily linear relation, a one-sided (negative) Bayesian Kendall’s tau correlation test was used (van Doorn, Ly, Marsman, & Wagenmakers, 2018). In the Netherlands, we found τ = −0.010, 95% CI [−0.074, 0.052], BF-0= 0.08 (i.e. BF0- = 12.24). This qualifies as strong evidence for the null hypothesis. In the US, on the other hand, we found τ = −0.144, 95% CI [−0.210, −0.078], BF-0 = 1185. This qualifies as extreme evidence for the presence of an inverse relation between general feelings of personal control and belief in a controlling God.

References

Alper, S., & Sümer, N. (2017). Control deprivation decreases, not increases, belief in a controlling God for people with independent self-construal. Current Psychology, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9710-9

Gronau, Q. F., van Erp, S., Heck, D. W., Cesario, J., Jonas, K. J., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2017). A Bayesian model-averaged meta-analysis of the power pose effect with informed and default priors: The case of felt power. Comprehensive Results in Social Psychology, 2, 123–138.

Heck, D. W., & Gronau, Q. F. (2017). metaBMA: Bayesian model averaging for random- and fixed-effects meta-analysis [R Package]. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/package=metaBMA

Jeffreys, H. (1939). Theory of Probability (1st ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., McGregor, I., & Nash, K. (2010). Religious belief as compensatory control. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 37–48.

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Napier, J. L., Callan, M. J., & Laurin, K. (2008). God and the government: Testing a compensatory control mechanism for the support of external systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 18–35.

Kay, A. C., Moscovitch, D. A., & Laurin, K. (2010). Randomness, attributions of arousal, and belief in God. Psychological Science, 21, 216–218.

Kay, A. C., Shepherd, S., Blatz, C. W., Chua, S. N., & Galinsky, A. D. (2010). For God (or) country: The hydraulic relation between government instability and belief in religious sources of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 725–739.

Kay, A. C., Whitson, J. A., Gaucher, D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Compensatory control: Achieving order through the mind, our institutions, and the heavens. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 264–268.

Lee, M. D., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2013). Bayesian cognitive modeling: A practical course. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

Scheibehenne, B., Gronau, Q. F., Jamil, T., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2017). Fixed or random? A resolution through model-averaging. Reply to Carlsson, Schimmack, Williams, and Burkner. Psychological Science, 28, 1698–1701.

van Doorn, J., Ly, A., Marsman, M., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2018). Bayesian inference for Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient. The American Statistician, 72, 303–308.

Verburg, M., Huzarevich, J., Hughes, K., Thompson, J., Figueira, R., Conner Koreis, C., … Riordan, C. (2016). Who’s in control: You, God, or government? Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/25280097/Whos_in_Control_You_God_or_Government. (Poster)

About The Authors

Suzanne Hoogeveen

Suzanne Hoogeveen is a PhD candidate at the Department of Social Psychology at the University of Amsterdam.

Eric-Jan Wagenmakers

Eric-Jan (EJ) Wagenmakers is professor at the Psychological Methods Group at the University of Amsterdam.