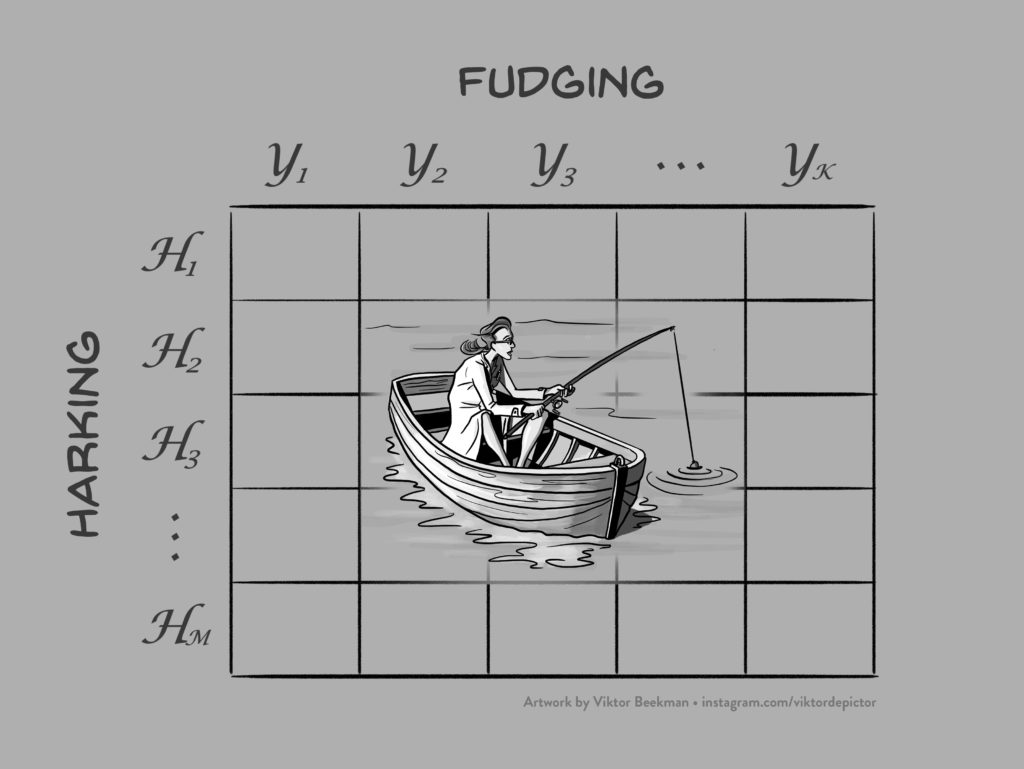

The Case for Radical Transparency in Statistical Reporting

Today I am giving a lecture at the Replication and Reproducibility Event II: Moving Psychological Science Forward, organised by the British Psychological Society. The lecture is similar to the one I gave a few months ago at an ASA meeting in Bethesda, and it makes the case for radical transparency in statistical reporting. The talking points, in order: The researcher…

read more